In the face of finite resources and mounting landfill, Timothy Allan wants to change the future, through innovative design that has the end in mind.

By Hannah Bartlett, for Flint & Steel

What goes up must come down; You reap what you sow. If a butterfly flaps its wings in the Amazon...

They’re the clichés of consequence we’re all too familiar with, and yet when it comes to products and to innovation, our measure of impact often doesn’t extend beyond our own front doorstep, or our rubbish bins on the footpath.

But our shortsighted expectations about what a newly-created product should and could be, might not only have negative environmental implications, but could also be hindering the innovative horizons we could be exploring.

The two-wheel electric Ubco bike has been developed to be emission-free, lightweight, and sustainable, using materials that can be reused and repurposed, and minimise environmental impact.

It’s been pitched at farmers and tourism operators predominantly, and it’s causing a fair bit of buzz. Debuting at Fieldays 2015, a TVNZ Breakfast reporter filmed herself hooning around on it, and just recently the New Zealand Herald reported acceleration in the bike’s production to meet demand in the North American market.

But the really interesting story is the one that led to the Ubco bike’s development. It’s a part of life that’s universally understood—all good things come to an end. For Tim Allan of Locus Research, this isn’t a throwaway statement; it underpins his entire design process. In working with developers and innovators, including those of the Ubco bike, Tim is committed to developing the most effective, efficient, and sustainable products possible—from beginning to end. For Tim, it’s not a case of making trade-offs between sustainability and good design, instead it’s a matter of problem-solving and innovating in such a way to make products that do both.

And while this may seem like an obvious goal for a designer, Tim explains that so often the integrity needed to see this approach through from start to finish is lacking in the leadership of many companies.

But rather than spending his time critiquing others, Tim’s approach is to lead by example. He’s part of an emerging group of New Zealand innovators who want to see a shift in the way we approach product design—to flip the process on its head and think about the end, as well as the beginning, and everything in between. To plan for the end, and to take responsibility for where a new product will end its life, before it’s even left the design phase.

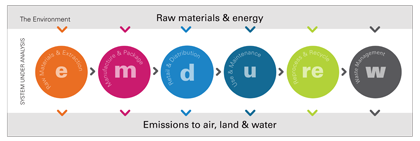

Tim explains by drawing a diagram showing the full life span of a product, including its initial conception, right through to what happens to it when a consumer decides it’s done its dash.

At every point along the way, energy and materials are used as “inputs” and in doing so they produce “outputs.”

In other words, it’s a lot more complicated than mere CO2 emissions or the recyclability grade on the end product, which many of the more common environmental management systems used

in the sustainability auditing process focus on. Tim and his team believe that products that are sustainable aren’t just better for the environment, they’re better products, full stop.

The Ubco bike is an excellent example of that. Farmers are jumping on board because one of the benefits of an electric bike is that it’s quiet, which as it happens, makes it far more practical than its noisy, gas-guzzling counterparts when it comes to herding stock. The choice of sustainable materials also makes it lightweight, for easier manoeuvrability, and being a two-wheeler, it’s a lot safer than the likes of the notorious quad bike.

In order to find the sweet-spot between smooth design and environmental cost when developing a product like the bike, the Locus Research team identify what the “functional unit” of a product is. In other words, what does this thing actually need to do? Tim says that by reducing something to its core function, you’re no longer confined to a preconceived idea about what the product looks like or how it fits together, but focus instead on what it needs to achieve. And as they begin to work through that, the team refuses to forge ahead with any stage of production without considering its impact on the environment.

This is because Tim is acutely aware that everything has an impact. He says any company that claims to be perfect is lying.

While nature has an auto-correct function in all its processes, humans often fail to measure the impact of the deeply rooted processes they have developed, and take a lot for granted. Especially when no one’s watching.

At Locus, they work with a model that looks at eight top-level impact categories used to identify the toxicity and environmental impact of a product, from the impacts of chemicals and toxins on humans, through to carbon emissions. Their level of detail and attention to improvement in this area goes beyond the common approach to environment management systems, including the “ISO 14001” standard adopted by many companies, which Tim says allows organisations to pick and choose which categories they will focus on improving.

It’s this attention and understanding of the opportunities presented in each stage of the life cycle that sets Tim’s approach apart, and give his products an innovative edge.

These constraints force creativity and as Tim says, “when you run a business holistically, it’s not surprising that it works out better for all concerned.”

It’s an understatement to say he’s cautious about companies who adopt environmental policy or procedure that sits on the surface—primarily serving a public relations function. “The way that people often discuss sustainability, it’s often not in the perspective that it’s the right thing to do. Either it has to save money, or it’s a PR thing.” Tim maintains that “it’s the right thing to do” so companies should “just do it.”

Tim laments when companies have some good initiatives, but don’t have a holistic approach and commitment to do things right, all the time. This is especially true when it comes to end-of-life management. He says some of the largest manufacturers in the world, especially of technology, trace as little as 5% of where their products end up.

In New Zealand, people can throw a cellphone, battery, or even a laptop in the rubbish and not be fined or held accountable for it.

With some of the world’s most valuable resources contained in the electrical technology that is so blithely thrown away, Tim says there are wasted opportunities for them to be reused, rather than ending up seeping toxins into a landfill. He says companies often have the resources to find creative solutions, but there is no will or pressure to do so.

“It’s a little bit like running an overdraft, we’re all spending the money and we’re accumulating all this stuff, but it actually has to go somewhere,” says Tim.

In other words, everything has a cost, and someone, somewhere will have to pay it.

Just as spending up large on a credit card for short term gain only leads to heartache later on, so too does creating products with no contingency plan as to what problems their existence might create for future generations, leaving them with an inherited debt of environmental cost.

Passing the buck doesn’t help either, with offshore rubbish heaps, third world “recycling” dumps, and floating rubbish islands—the stuff of nightmares come about due to a lack of global regulation.

For this reason, Tim says legislation is needed to ensure companies take responsibility for their products’ disposal. “With end-of-life, you need political force. Leadership will change everything. It will give [companies] permission to change things. The danger of just a voluntary code of sorts is that you’ll always have those who will continue to take short cuts and produce poor quality, unsustainable products.”

Introducing legislation around end-of-life, as has been done in Europe and Australia, levels the playing field for all companies and ensures some don’t cut corners. It sets up the framework and makes it a priority, giving developers working in product innovation the impetus and mandate to ensure it’s a priority built into their design from the get-go.

“If you like New Zealand and you like the way it is, then you need to take responsibility for the things you do, whether you’re a business or an individual.”

The worst thing people can do is throw their hands up and think it’s all too hard, says Tim.

“When you sit around and just talk about the problem, that is the problem.”

For too long our collective approach to environmental sustainablity has been about describing the problems, and making excuses. Instead, those who share a “just do it” philosophy are calling on people in all areas of society to be intentional about what they do. Whether it’s creating a better product, just because it’s better, or taking time to responsibly dispose of an unwanted good; not because you have to, but because it’s the right thing to do.

While Tim Allan waits for legislation to catch up and to enforce collective responsibility, he and others like him are calling on New Zealanders to do their bit. To remember that no action is without consequence, and that we all play our part in the cycle.

______________

This article appeared in Flint & Steel | Volume 03 – on sustainability and what we leave behind, and is reprinted by permission of the publisher, Maxim Institute. Check out the magazine at flintandsteelmag.com.

Comments

Post new comment